Executive Order on Cybersecurity: Don’t Crawl, Walk, or Run — Fly!

Before taking off, you should have your pre-flight checklist in place.

By: Matthew Karnas

Published on Jul 19, 2021Who hasn’t uttered the phrase “let’s crawl, walk, and run…” when starting a new initiative? A slow then fast approach makes sense; start small, get the process right, and start accelerating at a larger scale. But here’s the thing: it might seem counterintuitive, but it’s not always the right approach.

In the private sector, taking too long to implement a strategic initiative could put an organization at a disadvantage to its competitors. In the public sector and specific to cybersecurity, the crawl, walk, and run methodology can put an agency at a disadvantage to its attackers. The Executive Order is focused and understandingly aggressive in its expectations, but realizes business as usual won’t hit the mark, as in the first section it states, “incremental improvements will not give us the security we need; instead, the Federal Government needs to make bold changes and significant investments to defend the vital institutions that underpin the American way of life.”

Resources and time are factors working against Federal agencies in successfully realizing the actions stated in the executive order.

In preparation, Federal agencies can execute on a few key and foundational tasks in the areas of “intel information sharing,” “cloud and zero trust,” and “detection and response.” Federal agencies will also need to re-think their approach to resources from a personnel and execution perspective. Below are a few topic areas from the executive order with preparational tasks to provide insight from an agency perspective.

Intel Information Sharing

Information technology (IT) and operational technology (OT) service providers have the needed insight into cyber threats and incident information. Still, some current contractual obligations and conflicts are preventing the appropriate data sharing with Federal agencies. The executive order will reduce contract barriers and require service providers to share relevant threat and incident information with multiple agencies.

Reducing contractual barriers is a positive step, but after the obstacles are removed, the question becomes how does an agency effectively utilize that information. Many fingers are pointing to the following open standards as the fundamental building blocks:

- Structured Threat Information Expression (STIX): structured language for threat intelligence

- Trusted Automated Exchange of Intelligence Information (TAXII): protocol for communicating cyber threat information

- Open Command and Control (OpenC2): providing a common language, vendor agnostic communication across a wide range of cyber tools.

- Collaborative Automated Course of Action Operations (CACAO): standardizing and automating SOAR playbooks.

These are just open standards; more importantly, do agencies have the right processes and technologies. In reality, not all agencies are at a point of maturity to adopt all of these standards and might not fully leverage existing data sources.

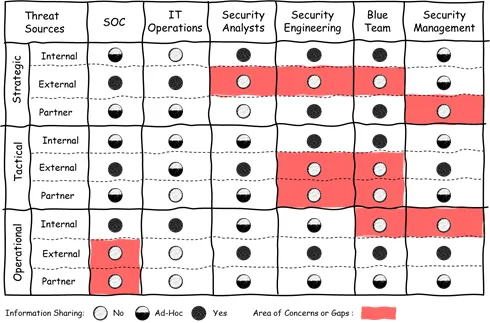

Take stock of the current cyber threat intelligence program in place, such as data sources consumed, who is using the data, and where the program should be over the next year 3-, 6-, and 12-month period. Consider performing the following:

Create a matrix to understand better the data sources in use and who is using the data. On the matrix, the Y-axis represents the three types of threat intelligence (strategic, tactical, operational) per data source (internal, external, partner). The X-axis represents various teams that could utilize threat intelligence (SOC, NOC, IT Operations, Security Analysts, etc.). Label each square with a current status (i.e., 1: In Use, 2: Partial Use, 3: Not in Use) and color code each squared as an indicator (i.e., green: No Concerns, orange: Some Concerns, Red: Critical).

Cloud and Zero Trust

The Federal Government realizes it needs to change its current approach to cybersecurity and the underlying technology in use. As the executive order states, “the Federal Government must take decisive steps to modernize its approach to cybersecurity…adopt security best practices; advance toward Zero Trust Architecture; accelerate movement to secure cloud services….”

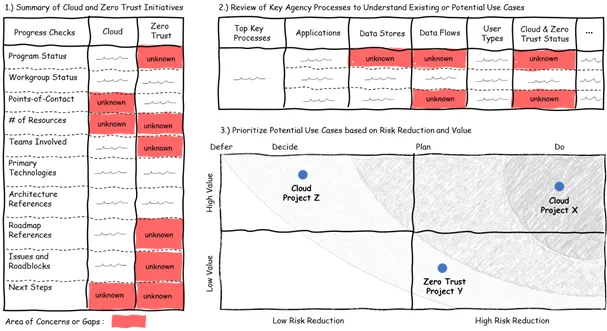

The migration to cloud technology and implementing a zero-trust architecture are heavy lifts and should be considered ongoing efforts. There is no easy button, especially in large, diverse technology environments with legacy and technical debt. Zero trust has unfortunately become a marketing buzzword, with many cyber vendors claiming zero trust capabilities. There isn’t one product or solution that implements zero trust principles and will require support from multiple groups in and out of security at an agency. Zero trust principles are difficult to implement in a legacy environment and as Agencies start building and utilizing cloud services, this is the opportunity to introduce such principles. It is important to understand an Agency’s cloud infrastructure and approach to coordinate activities with potential zero trust efforts.

To better understand the Agency’s current status around cloud infrastructure and zero trust initiatives consider performing the following: 1.) Create a summarized list for both cloud and zero trust with workgroup status, technologies in use, resources supporting efforts, number/percentage systems that have been migrated, agency defined principles, security architecture references, and current roadmaps, main points of contact. 2.) Develop a spreadsheet of critical agency processes, applications, data types, data flows, and users to understand potential use cases for cloud migration and zero trust implementation. Include attributes such as purpose, essential process category, risk assessment rating, criticality to the mission, categories of users, # of users, network location, internal/external facing, the sensitivity of data, authentication type, authorization type, application type, key technologies, networking tools, logging, and monitoring status, etc. 3.) In coordination with the working groups within the Agency, create a value/risk reduction matrix to support prioritizing potential use cases.

Detection and Response

Continuous monitoring of threats, early detection from abnormal activities, and timely and comprehensive responses have become essential requirements to security teams and are a significant part of the executive order. Continuous monitoring not only includes endpoint detection and response (EDR) solutions but also a threat hunting program to improve the overall ability for detecting unique threats at an agency. Federal Agencies will also be required to standardized incident response playbooks to provide more comprehensive responses across agencies.

Let’s be clear; an EDR initiative is not a project; it’s a program that will require ongoing care and feeding. Therefore, an agency with immature, limited, or non-existent EDR and threat hunting programs will need to have the appropriate capital and operational expenditures to support the initial implementation and ongoing active support. Also needed for an effective EDR program is asset coverage; if an agency doesn’t have a grasp on its endpoints or has a manual process for identifying and managing assets, the effort put in place for the EDR program won’t represent the results. While standardizing incident playbooks could provide some benefits, it could also potentially muddy incident responses for each Agency by genericizing procedures. Each federal Agency has security teams organized in different manners, has differing technologies, and supports various missions.

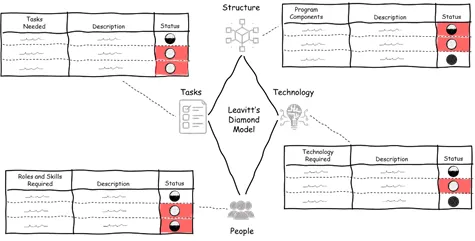

To better understand the current state of your Agency’s EDR program, threat hunting program along with playbook status, utilize Leavitt’s Diamond model. Leavitt’s Diamond model incorporates structure, people, tasks, and technology, in which all four pieces are interconnected, creating the shape of a diamond. Structure represents the pieces or components of the program that are required for success; people include the roles, skills, and educations needed; tasks are the day-to-day activities that need to be fulfilled; and technology represents the tools that are required to perform those tasks. For each of the following areas of EDR, threat hunting, and incident playbook, create a Leavitt’s Diamond and identify current capabilities along with a color code as an indicator of potential gaps.

Wrapping it Up and Taking Off

As discussed earlier, the Federal Government, based on the Executive Order, realizes business as usual won’t hit the mark regarding protecting our national institutions. Crawl, walk, and run methods will not promote the changes required to affect the Federal Government’s security posture in a meaningful way against known and unknown attackers. In preparation for making significant changes at a quicker pace, Agencies can be proactive and start preparing through the following tasks:

Intel Information Sharing:

- Determine what intel data sources are in use and who is using them with a matrix.

- Prioritize the steps to optimize the current threat intel program.

Cloud and Zero Trust:

- Determine the current status of cloud use and migration and zero trust principles within your organization.

- Principles for cloud and zero trust can’t be created in a vacuum; no one model fits all Agencies. Review the Agency’s specific critical processes, applications, data, and specific attributes to support decision making.

- After reviewing principles and critical processes, use a value/risk reduction matrix for planning purposes.

Detection and Response:

- Understand current the current state of EDR, cyber threat hunting, and playbooks within your Agency by summarizing structure, people, tasks, and technology for each area.

Here is one last thought on what’s needed to be successful based on the requirements from the Executive Order. Fail fast. Incremental changes and crawl, walk, run methods need to be replaced with fail fast. Fail fast principles will require re-thinking how the Federal Government organizes projects, programs, staffing, and contracts. When going through these exercises, ask yourself if the Agency can fail fast and what can be done to restructure tasks in such a manner.